In opposing nuclear energy environmental groups draw on a wealth of imagery and deeply ingrained fears. There is no better demonstration of this than simply uttering the words Chernobyl and Fukushima. We all know these words and the fear they instill. Rigorous scientific analysis may show that the dangers from burning coal are vastly greater than those of nuclear energy; but can you can name a single coal power plant?

This willingness to draw on, and to strengthen, deep cultural fears sadly is coupled with a willingness to draw on remarkably dubious scientific studies. Mainstream scientific analysis is too frequently ignored in favour of reports from the fringe. Here we see that climate change deniers are not unique in their treatment of evidence.

One such report is that by the German actuarial firm Versicherungsforen Leipzig into the insurance costs of nuclear energy. This report, funded by the biggest German renewable energy lobby group, has been cited by Friends of the Earth, Greenpeace, and such high profile figures of the British green movement as Jonathan Porritt, Tom Burke and Tony Juniper. It regularly forms a key piece of evidence to back up arguments that nuclear energy is too expensive. Yet, its contents are impossible to defend.

The conclusions of this study are relatively clear. If nuclear energy has to account for its true insurance costs then it will become deeply uneconomic. And the numbers they present are hard to argue with on first glance. It should cost between €0.139 and €2.36 per kWh of electricity generated to insure the average nuclear power plant.  This alone is double the wholesale electricity price in most countries. Nuclear energy then makes no sense, unless we fool ourselves that these external costs do not exist.

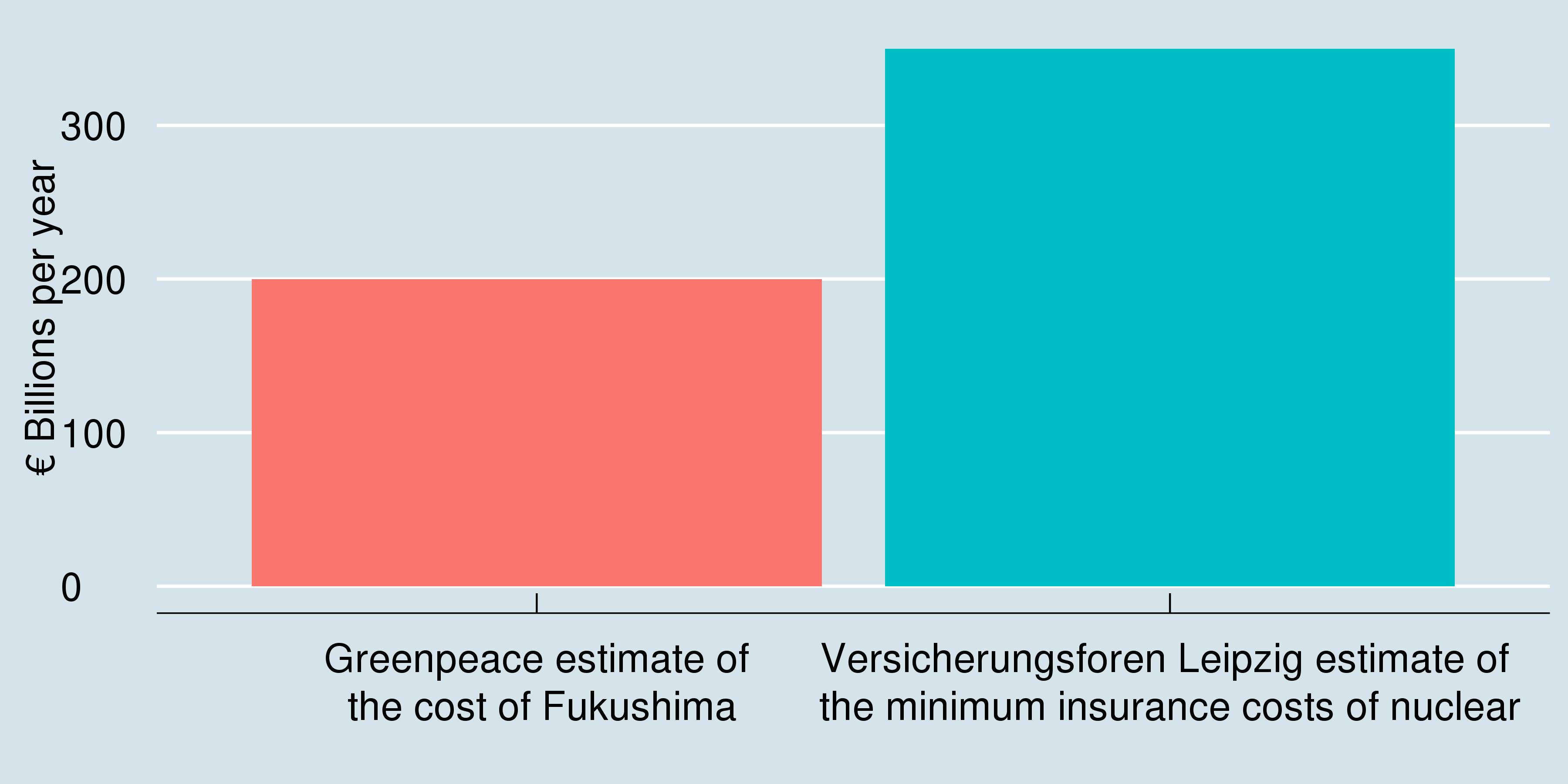

But let us consider these figures. Last year, the world's nuclear power plants produced 2,500 TWh of electricity. If each plant paid €0.139 per kWh in insurance, the total insurance fees would be €350 billion.

This sounds remarkably high for a lower estimate of the insurance costs of nuclear energy. And it is. How much will the Fukushima disaster cost? Here I will turn to Greenpeace, an organisation one could not accuse of underestimating the costs of nuclear energy. They tell us that Fukushima will cost $250 billion. This is €200 billion in today's conversion rates.

In other words this study is assuming that a Fukushima scale event should be occurring each year. And this is only to get to their minimum insurance fee. The maximum estimate would require an astounding €5.9 trillion in insurance fees each year. This is greater than the total annual GDP of Japan.

Given that these numbers are on the face of it nonsensical, one must ask where they come from. The report itself lasts one hundred pages; just long enough to convince people it is a serious and detailed piece of work, and just long enough to put anyone of actually reading it.

But on reading the list of contents I was immediately intrigued by what it said about terrorist attacks on nuclear power plants. This section tells us all we need to know about the study's intellectual rigour.

We know some basic things about the likelihood of a terrorist attack on a nuclear power plant. The first is that there has never been one, and there appears to be no evidence that a plan to attack a nuclear power plant has ever moved beyond the basic planning phase in any terrorist group.

The reasons for this are relatively clear. Attacking a nuclear power plants would be an exceedingly difficult affair, and only the most sophisticated or delusional terrorist organisation would even dream of doing it. There are far easier targets. For this reason we should be skeptical of claims about potential terrorist attacks on nuclear power plants.

What does this report say? On page 61 we find the following:

"Terror risks are a special kind of disaster risk, since they do not occur by chance but rather as a result of deliberate human action. This means that it is impossible to use data and processes to model the probability of occurrence of damage or associated perils brought about by terror risks".

Estimating the probability of a terrorist attack on a nuclear power plant is impossible. We are then told that the probability of a terrorist attack is "1:1,000 per operating year."

This statement about probability - a probability we are told is impossible to estimate - is offered up without explanation or any supporting evidence. Now, as Christopher Hitchens said, what can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. But perhaps I should explain the full absurdity of this probability.

Here are the simple logical consequences of this one in a thousand probability of attack:

- A typical nuclear power plant will have a 4% probability of being attacked by terrorists during its lifetime.

- There is an almost 40% probability of a terrorist attack on one of the world's 435 nuclear power plants each year.

- The probability of there having been a terrorist attack on a nuclear power plant in the last twenty years was approximately 99.9%.

Nuclear power plants are not attacked by terrorists every couple of years. And we have somehow managed to get through almost 60 years of civil nuclear energy without so much as a hint of one. Yet, these absurd numbers were presented in a report commissioned by Germany's largest renewable energy lobby group and appear to be taken at face value by most major environmental groups in Britain. Keep this in mind when these groups, rightfully, tell us to stop ignoring the science of climate change.

The risks posed by nuclear energy are real, and should be managed. But they must also be put in context. In his book Small is Beautiful, E.F. Schumacher pleaded with us to abandon nuclear energy; radiation, he told us, is "an evil of an incomparably greater 'dimension' than mankind has known before." Schumacher's alternative was to reconsider the benefits of conventional sources of energy; and by that he meant coal. He asked us to replace an imagined existential threat with a real one. And many continue to do so.

Authored by:

Robert Wilson

Robert Wilson is a PhD Student in Mathematical Ecology at the University of Strathclyde.

His secondary interests are energy and the environment and writes on these issues at The Energy Collective.

Follow him on Twitter: @PrimedMover

Email: robertwilson190@gmail.com

There's a chance you are qualified for a new government solar energy rebate program.

ReplyDeleteFind out if you're qualified now!