There’s a lot of talk in California these days about imposing fixed monthly charges on residential electricity bills. The large investor-owned utilities in California have small or no fixed charges,[1] instead collecting all of their revenue from households through usage-based charges, called volumetric pricing. (And those volumetric prices increase steeply with your monthly usage, the “increasing-block pricing†approach that I discussed in September.)

Interestingly, one of the three natural gas distribution companies in California has a fixed charge, but the other two don’t  (SoCal Gas has a charge that is about $5/month.  Feel free to chime in if you know how this difference came to be.) Most other electric utilities in the U.S. do charge some fixed monthly fee for being hooked up to the electric grid.

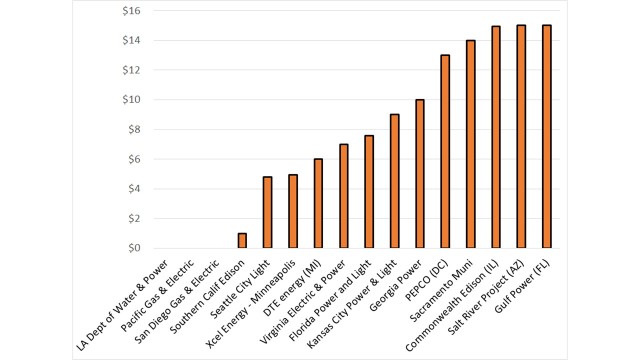

Fixed monthly charges at regulated and muni utilities (randomly selected outside CA)

Fixed monthly charges at regulated and muni utilities (randomly selected outside CA)

Fixed charges are often justified based on the utility having fixed costs. The connection seems logical at first glance, but when you look closer it’s more complicated.

Fixed costs fall roughly into two types: customer-specific and systemwide. When having one more customer on the system raises the utility’s costs regardless of how much the customer uses â€" for instance, for metering, billing, and maintaining the line from the distribution system to the house â€" then a fixed charge to reflect that additional fixed cost the customer imposes on the system makes perfect economic sense. The idea that each household has to cover its customer-specific fixed cost also has obvious appeal on ground of fairness or equity.

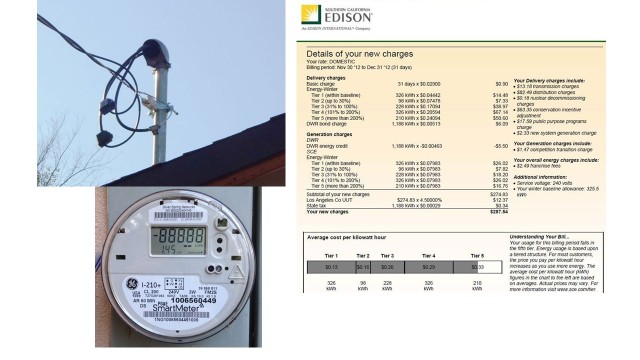

Customer-specific fixed costs from things like metering, billing, electric drop to house

Customer-specific fixed costs from things like metering, billing, electric drop to house

But much of the utility fixed costs that are being discussed are systemwide â€" such as maintaining the distribution networks in residential neighborhoods. These costs wouldn’t change if one customer were to drop off the system. In other words, running the system as a whole has certain unavoidable costs and someone has to pay them. There isn’t much guidance, based on economics or equity, about who should pay, because there is no “cost causation†as it is termed in the utility world.   In particular, the statement I have heard a number of times recently that “the utility should cover fixed costs with fixed charges†has no basis in economics when it comes to system fixed costs.

Before we discuss how to pay for system fixed costs, let’s step back and remember where economics does provide a valuable guide, that is, in setting the price of an incremental or marginal kilowatt-hour.  The price for a marginal kilowatt-hour should reflect the full “societal†marginal cost of providing that electricity, meaning that it should include the industry’s marginal production costs plus the marginal externality costs imposed on others outside the production process, like the cost of greenhouse gases that are released. The idea is that if you don’t place a value on the good that is at least as great as the full cost of producing it (including the pollution it creates), then society shouldn’t allocate resources to produce it for you.

If you don’t think about it too hard, you might conclude that if the marginal (or volumetric) price just covers marginal cost, then what is left over is fixed costs, so fixed charges “should†cover fixed costs.

But there are at least three good reasons to think harder about it.

First, the marginal cost that the utility faces is less than the full marginal cost it imposes on society when it produces electricity because the utility does not have to pay the full social cost of the pollution it produces â€" including NOx, particulates, and greenhouse gases.[2]

If the utility charges a price that covers the full marginal cost including all the externalities, but doesn’t itself actually have to pay for those externalities, then it generates extra revenue. That revenue can go towards covering fixed costs.  That lowers the fixed charge necessary to cover costs while at the same time setting appropriate marginal prices.[3]

Second, as everyone who studies electricity markets knows (and even much of the energy media have grown to understand), the marginal cost of electricity generation goes up at higher-demand times, and all generation gets paid those high peak prices. That means extra revenue for the baseload plants above their lower marginal cost, and that revenue that can go to pay the fixed costs of those plants, as I discussed in a paper back in 1999.

The same argument goes for transmission lines, where price differentials between locations mean that the transmission line generates revenue above its marginal cost (which is effectively zero), and can go to pay the fixed costs of transmission lines. In fact, the fixed costs of generation and transmission should generally be covered without resorting to fixed monthly charges.

The same is not true, however, for distribution costs. Retail prices don’t rise at peak times and create extra revenue that covers fixed costs of distribution. That creates a revenue shortfall that has to be made up somewhere. Likewise, the cost of customer-specific fixed costs don’t get compensated in a system where the volumetric charge for electricity reflects its true marginal cost.

But unlike customer-specific fixed costs, there isn’t a strong fairness or economic efficiency argument for recovering fixed distribution costs â€" which are not customer-specific â€" through a fixed monthly charge.

Programs subsidizing high-efficiency light bulbs, refrigerators and washing machines may be a great idea, but they still create fixed costs that ratepayers have to cover

And then there are sunk losses from the mistakes of the past, such as expensive nuclear power plants and high-priced contracts signed during the California electricity crisis.  And don’t forget ongoing expenses that are not directly part of the electric utility function, like energy efficiency. Someone has to pay for those subsidies on new refrigerators and clothes washers.[4]

That brings us to the third reason to think hard about fixed charges: fairness and distributional considerations. If customer A uses 10 times more electricity than customer B, should they pay the same share of the system fixed costs? And, by the way, customer A is on average wealthier than customer B. My informal poll suggests most people think customer A should pay more.

But any approach that is based on usage amounts to raising the volumetric price further, after we have already raised it to reflect the real externalities. Doing that encourages inefficient substitution away from electricity. Yes, there can be such a thing as too much energy efficiency investment (take a look at the cost of retrofitting windows). Nor does it really help society when high marginal prices incent households to install solar just to shift fixed costs to others. And, of course, Max recently blogged about how high marginal electricity prices discourage EVs.

And that’s where it can make sense to resort to fixed monthly charges to cover at least part of the shortfall.  Fixed charges may be the least bad way for utilities to balance their books without setting volumetric electricity prices so high that they unreasonably distort behavior.

But the mere existence of systemwide fixed costs doesn’t justify fixed charges. We should get marginal prices right, including the externalities associated with electricity production. We should use fixed charges to cover customer-specific fixed costs. Beyond that, we should think hard about balancing economic efficiency versus fairness when we use additional fixed charges to help address revenue shortfalls.

I tweet energy news articles, and the occasional research article, nearly daily @EnergyClippings

â€"â€"â€"â€"â€"

[1] PG&E and SDG&E have no fixed charge, SCE’s is $0.99/month. All three have a small minimum bill, less than $10,  which is binding on extremely few customers.

[2] What’s that you say? that California utilities already have to cover their GHG emissions in the state’s cap-and-trade market? Oh please. First, the utilities are given free permits to cover most of their emissions. Second, the regulatory agency (CPUC) has said publicly that it will not allow GHG costs to raise residential rates. And, finally, do you really think the current price in the cap-and-trade market of $12/ton â€" an amount that will lead to virtually zero change in production or consumption behavior â€" covers anything like the full cost of the GHG emissions? It’s less than one-third of the U.S. government’s estimate of the true externality cost  (which I think is likely still too low).

[3] Of course, if we ever get to actually charging polluters for their emissions, then this source of extra revenue to the utility will go away. That will still be a happy day for me.

[4] Please, save the comments arguing that energy efficiency programs pay for themselves. They may save society as much or more in energy resource costs as they cost the utility, but when it comes to rate making, the money for those programs comes from ratepayers, and energy efficiency programs don’t justify a volumetric rate increase on economic grounds.

No comments:

Post a Comment